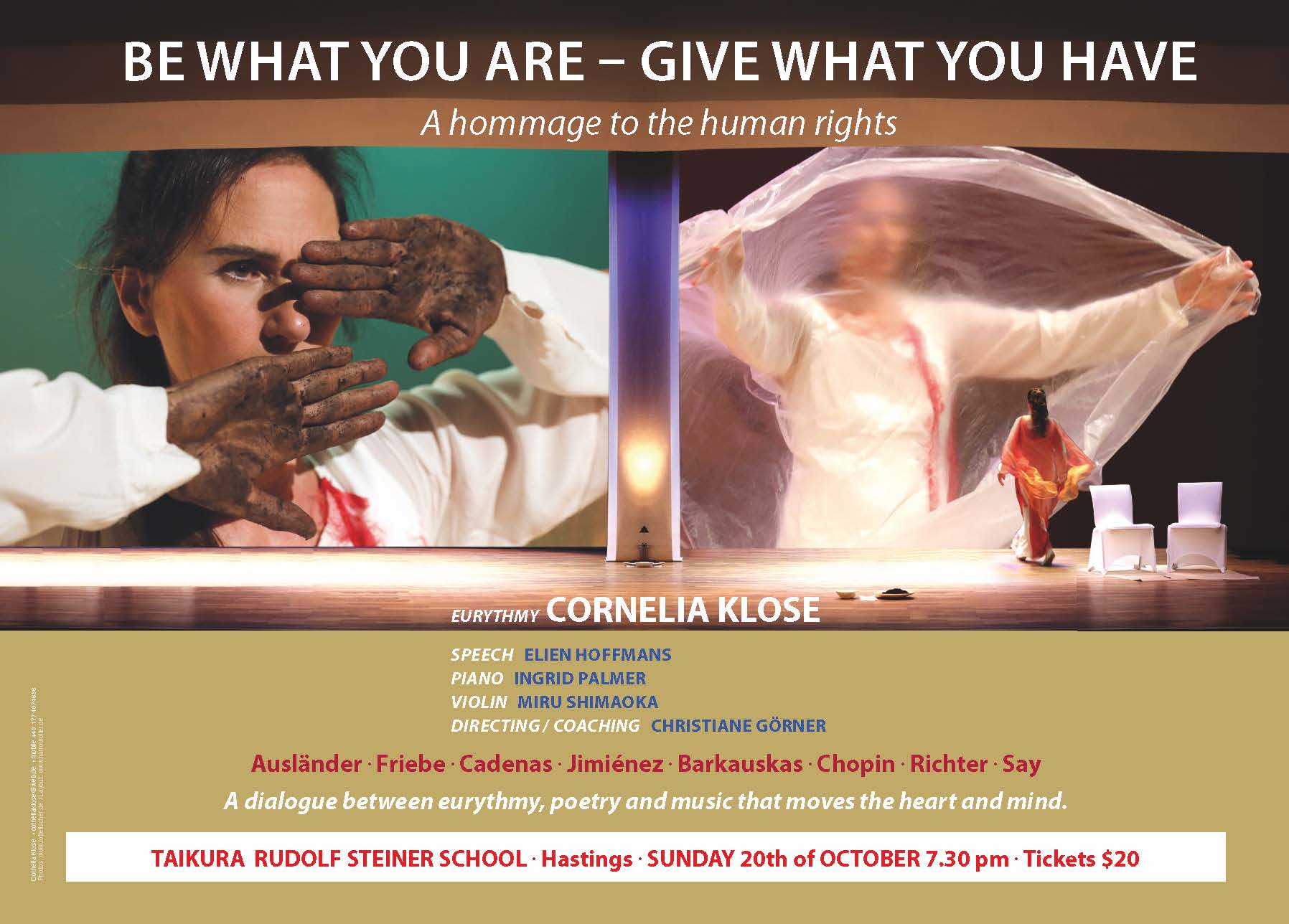

News 42: 20 OctoberAnthroposophy in Hawkes BayNewsletter 42-24 for Sunday 20 October 2024 Calendar of Coming Events-- Diary Dates In the Rudolf Steiner Centre, 401 Whitehead Road, Hastings

The Years between Seven and FourteenBy Erich Gabert (a teacher of the original Waldorf School under Rudolf Steiner) The inner condition of children in the second seven-year period has come considerably closer to that of grown-ups. That deepest layer, that is, the bearer of the element of life, of habits and the temperaments, has by approximately the age of seven acquired a certain independence with regard to the surrounding world. This organism of life-forces in the child, his "ether-body", has released itself from that of the grown-up, as the physical body did seven years previously; it has been "born". However, all those inner experiences that, though one cannot call them completely conscious in the actual sense, certainly approach much closer to full consciousness, namely the forces that strictly speaking we are in the habit of calling "soul" processes, still remain "unborn". As far as these forces are concerned, during the years that follow now, there is still absolutely the same kind of relationship to the grown-up, the same intimate, non-volitional and unconscious connection and unity with them, which abundantly justifies the comparison with the condition during the months before birth. Although the actions of the grown-ups do not pass irresistibly and unchanged in the life and action of the child any more, certainly all the soul stirrings and particularly the less conscious ones, still pass directly into the child. Joy and sadness, gaiety and worry, calm certainty and tense restlessness are still conveyed to the child as though by a subterranean conductor and shared by him in experience without being consciously perceived. The child nourishes itself on that which passes through the soul of the grown-ups, and builds up its own soul forces with it, just as it nourished itself before birth from its mother's body and in the first seven years of its life from the body-building life forces of the people in its surroundings. For this kind of connection between child and adult, which in itself can be clearly observed and described, there is also no usable really apt term. Rudolf Steiner used the word "authority" for it most often, but one must always take into account that this expression is taken over from connections and dependence among grown-ups. When it is applied to children one must translate the word "authority" further down into the realm of the subconscious, where things happen naturally, as a matter of course, in the same way as was done for the younger child with respect to the word "imitation". In his attempt to make understandable these facts of the inner being of the child, Rudolf Steiner has also resorted here to traditional expressions, and has applied the expression "astral body" to the organism of soul experiences, to this totality of an interconnected structure. He spoke accordingly of a still existing "un-bornness of the astral body" for this second seven-year period, the birth of these forces occurring then around the 14th year. The knowledge of these two facts — the independence of the life forces (birth of the ether body) which occurs with the change of teeth on the one hand, and the close connection of the soul life (pre-natal condition of the astral body) that continues up till puberty, on the other hand, — really puts the key into the teacher's hand for the understanding of the age from 7—14 years. This is proved right into every detail of the measures used in education and in lessons; and especially on the subject of moral education that concerns us here. The actively engaged teacher will have no difficulty in varying, augmenting and completing the few indications that can be given here. The fact, that around the 7th year the organism of life forces becomes more independent, has the result that now what the child sees the grown-ups doing no longer can or has to flow over so directly into his own actions and will. The child takes, as it were a step back from the world and other people. He perceives them and fashions what he sees into inner pictures. He lives in these pictures with his soul, and not until this point does the effect on the active will occur. The inner world of pictures pushes its way in, so to speak, between the world of the activities of the grown-up and the actions of the child, as something belonging to him. Simply doing the right thing in front of the child loses its magical force. Instead, however, the inner picture-making activity is approachable by educational help, and in need of it. "The child longs for pictures" Rudolf Steiner once said. That applies to all teaching activities, to all lessons, and certainly applies to moral education too. For now, in the type of inner picture that one gives the child or that one causes to arise in him, one has a new means of working deeply and strongly into his actions to guide and help him in his one-sidedness, naughtiness and difficulties. It has, for instance, been noticed again and again how extraordinary effective it is if one sets to work, according to some advice of Rudolf Steiner which one first of all perhaps faced with scepticism, namely to tell a child a story, which has been prepared to suit his own particular characteristics, habits and difficulties. If it is a matter of an egoistic, instinctively greedy child, one would perhaps tell him the old fable of the dog that goes over a bridge with a piece of meat in his mouth. Then he sees the meat reflected in the water. In his foolish greed he wants to have that as well, and snaps at it. But in that moment his piece of meat falls out of his mouth, falls into the water and now he has none left at all. Or for a child that finds it difficult to tell the truth one would tell the story of the liar whom nobody will believe any more, even when, for once, he does speak the truth. Many old fables and tales can be drawn on, and they are all the more effective the more vividly one works them out in detail, and the more impressively one tells them. It is much better still, though, if you dare to make up quite new stories for the child and the situation in question. However clumsy they may be at first, the teller's own inner participation will be much stronger and that is just what makes it so effective, because it goes directly over into the child. Now, one can develop the stories in two ways. On the one hand one can present the bad qualities to the child as characteristically and pictorially as possible, so that he has a thorough experience of their ugliness. One can, however, also show in the course of the narrative how a bad deed perpetuates itself ad absurdum. One can for instance invent, for a child that with blissful, timeless slowness arrives everywhere too late, a story of a snail that never comes to invitations until all the good things have been eaten up. Such a story can be told and retold many times. One can, however, also replace it before long by a similar one with the same idea. The more alive one’s own inventiveness is in this matter, the better. As has been said, it has proved itself repeatedly, how strongly this medium works at this age. It is, however, not at all necessary to stick to the images that are used as a deterrent, for one can achieve a lot by presenting the children with examples that are worthy of imitation, and others that actually tempt them to imitate them. Just this positive encouragement and enthusiasm will often have a better effect on the still rather tender moral strength than the merely negative. One can perhaps tell timid little mouse stories like "The Story of the Youth who went forth to learn what Fear was" or like the "Town Musicians of Bremen". And then when, in course of time, the transition is made from fairytales to myths and after that to the actual historical figures, then, more than ever, the most wonderful possibilities arise. Siegfried, Kriemhild, Achilles and Hector, Alexander the Great, Hannibal, Arminius from the point of view of his heroic deeds, Buddha, Socrates, St. Francis, St. Elisabeth in her striving for truth and humanity: the centuries are brimful of figures from whose descriptions the soul of the child can draw strengthening forces of good, not to mention all the all-surpassing pictures of the biblical stories. And the pedagogical intention can, at one and the same time, be a twofold one: one can tell the kind of stories to the children that have the effect, in general, of improving them and drawing out the good, and at the same time, one can pursue the intention of letting the stories work in quite a particular way on one or other child or on a group of children, to have an effect on certain attributes, and to work in the soul in a harmonising, calming, encouraging, arousing and purifying way. Many other things can be used in the same way. Maybe, if in the first animal period the teacher has been speaking about the bull and the cow and then sums it all up in a little dramatic scene, if he lets a boy with a tendency to blind rages take the part of the wild bull, it could perhaps calm him down noticeably and make him more sensible, at least for a while. And it would do a somewhat sleepy girl good to play the part of the cow. Besides, as long as the relationship of trust and natural, not forced, authority is there, it does not matter so much, if the child sees why it has to retell just that story, or play that particular part. Certainly, one may not, under any circumstance, do such a thing as preach about it, for then the effect would be gone at once. Helpful forces come especially from the unspoken words, even though all the participants know very well to whom it applies. It is similar with the practice, in the Waldorf Schools, to seat children of the same temperament together. It is sometimes uncomfortable, but just through the clash with similar one-sidedness, in which the child recognises itself as in a mirror, many a thing can be evened out which would otherwise lead to punishable offences or things not done properly. If a very phlegmatic 12-year old boy comes home and says to his mother: "Listen, Mother, now I am sitting by someone (with a shake of his head) who is just like me!" Then quite decidedly some wholesome shaking-up has taken place. All these pictorial experiences, in which the child's own being comes to meet him from outside as though in a mirror, work better the more strongly the soul of the teacher is active as mediator. For here the second main quality of this of 7 to 14 years comes to expression, namely that the child in its soul processes is still inwardly connected with the grown-up and dependent upon him. He feels those things to be beautiful and right, or good and worthy of love, which the grown-up to whom he is attached feels to be so. He sees the world through his eyes and in this way learns to see it better and better, the natural as well as the moral world. Therefore, such things as our examples of images and narratives that are aimed to influence the development of character should never be given except with the fullest most sincere inner participation of the teller. Then will his admiration and love for the personalities presented, or on the other hand his aversion, his contempt when it is a question of evil characters, pass directly to the children, and their capacity for moral sensitivity, their moral judgement, can be trained by this sharing of feeling and judging. This again holds good, too, just as much for the establishing of morals in general as for having an effect in particular on individual characteristics of certain children that specially need it. When the grown-up knows that all that is good and loving in his soul passes directly to the child, then he will strive more and more to let helpful, heart-warming, constructive and soul-nourishing feelings and thoughts grow and live in himself. He will try to keep all the criticising, intellectual, inharmonious and uncontrolled parts of his being away from the child. And if there is a child who especially needs it, he will fill himself inwardly with bold and daring feelings, or with feelings of helpfulness and devotion, so that these soul elements flow over into the soul of the child by way of that mysterious underground connection of the soul that one points to with the word authority. So, according to the teacher's strength of soul and of love it is certainly possible to succeed, more or less, in gently diverting and transforming dangerous tendencies before they lead to the sort of deeds and utterances that once they have happened can no longer remain without the compensating and consciousness-awakening effect of punishment. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Another sign from "Hidden Oasis" near Pune, India.

Posted: Sun 20 Oct 2024 |

| © Copyright 2026 Anthroposophy in Hawkes Bay | Site map | Website World - Website Builder NZ |