Goetheanum's Foundation Stone

As the double pentagonal dodecahedron, the heart of the Foundation Stone laid under the first Goetheanum and still under the second, is a geometrical form I am offering some musings on GEOMETRY in the intervening weeks, as background. RB

As related in his autobiography, "The Story of my Life" [GA28], Rudolf Steiner had a special connection to Geometry [p11-12]: here is the extract [p11-12]

"Soon after my entrance into the Neudorfl school, I found a book on geometry in the Assistant Teacher’s room. I was on such good terms with the teacher that I was permitted at once to borrow the book for my own use. I plunged into it with enthusiasm. For weeks at a time my mind was filled with coincidences, similarities between triangles, squares, polygons; I racked my brains over the question: ‘Where do parallel lines actually meet?’ The theorem of Pythagoras fascinated me.

That one can live within the mind in the shaping of forms perceived only within oneself, entirely without impression upon the external senses—this gave me the deepest satisfaction. I found, in this, a solace for the unhappiness which my unanswered questions had caused me. To be able to lay hold upon something in the spirit alone brought to me an inner joy. I am sure that I learned first in geometry to experience this joy.

In my relation to geometry, I must now perceive the first budding forth of a conception which has since gradually evolved in me. This lived within me more or less unconsciously during my childhood, and about my twentieth year it took a definite and fully conscious form.

I said to myself: "The objects and occurrences which the senses perceive are in space. But, just as this space is outside of man, so there exists also within man a sort of soul-space which is the arena of spiritual realities and occurrences." In my thoughts I could not see anything in the nature of mental images such as man forms within him from actual things, but I saw a spiritual world in this soul-arena. Geometry seemed to me to be a knowledge which man appeared to have produced but which had, nevertheless, a significance quite independent of man. Naturally, I did not, as a child, say all this to myself distinctly, but I felt that one must carry the knowledge of the spiritual world within oneself after the fashion of geometry.

For the reality of the spiritual world was to me as certain as that of the physical. I felt the need, however, for a sort of justification for this assumption. I wished to be able to say to myself that the experience of the spiritual world is just as little an illusion as is that of the physical world. With regard to geometry I said to myself: "Here one is permitted to know something which the mind alone, through its own power, experiences." In this feeling I found the justification for the spiritual world that I experienced, even as, so to speak, for the physical. And in this way, I talked about this. I had two conceptions which were naturally undefined, but which played a great role in my mental life even before my eighth year. I distinguished things as those "which are seen" and those "which are not seen."

I am relating these matters quite frankly, in spite of the fact that those persons who are seeking for evidence to prove that anthroposophy is fantastic will, perhaps, draw the conclusion from this that even as a child I was marked by a gift for the fantastic: no wonder, then, that a fantastic philosophy should also have evolved within me.

But it is just because I know how little I have followed my own inclinations in forming conceptions of a spiritual world —having on the contrary followed only the inner necessities of things—that I myself can look back quite objectively upon the childlike unaided manner in which I confirmed for myself by means of geometry the feeling that I must speak of a world "which is not seen."

Only I must also say that I loved to live in that world. For I should have been forced to feel the physical world as a sort of spiritual darkness around me had it not received light from that side.

The assistant teacher of Neudorfl had provided me, in his geometry text-book, with that which I then needed—a justification for the spiritual world.

In other ways also I owe much to him. He brought to me the element of art. He played the piano and the violin, and he drew a great deal. These things attracted me powerfully to him. Just as much as I possibly could be, I was with him. Of drawing he was especially fond, and even in my ninth year he interested me in drawing with crayons. I had in this way to copy pictures under his direction. Long did I sit, for instance, copying a portrait of Count Szedgenyi. …"

*****

Rudolf Steiner does not say what the name of the Geometry book was. It could well have been one written in 300 BC by Euclid, a Greek mathematician. Actually Euclid wrote his “Elements” on geometry in 13 volumes. He was not the first geometer to write about Geometry, but he collected and organised the work of all those before him from Pythagoras onwards. Amazingly, his work was used in education until well into the 19th Century (when RS was in school).

You can see that Rudolf Steiner experienced the elements of Geometry as pure ideas, and saw that thinking about them was spiritual activity. In his 30s, he writes a book called "The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity". He ensured that Form-drawing and Euclidean Geometry, including Platonic solids, were part of the Waldorf curriculum in the Lower school and that Conics, Trigonmetry, Algebraic Geometry, Calculus and Projective Geometry were part of the Upper School Curriculum.

Let’s look at the very beginning. In an early lesson in Grade 1, the teacher and then each child draw a vertical line downwards [a gesture of incarnation] on the blackboard. It’s an activity, an experience resulting in a 'picture' of the class as each line has been created by an individual child.

When a child draws a line with a pencil on a sheet of paper, the pencil is like an upright figure walking through the landscape led by the hand of the child whose will determines where it should go.

You, as onlooker, may see a straight line drawn by the point of the pencil on a the surface of a plain (blank) sheet of paper [a plane], but is thick and coarse compared with the pure idea which is infinitesimally thin, so thin that it virtually disappears from sight – it is only there in your imagination.

Anyway, here we have the three basic elements of Geometry:

Behind each word (in whatever language) stands a concept - a spiritual entity.

It is very interesting that each of these 3 words are not just reserved for use in Geometry, but have a variety or spread of meanings in popular language.

Take 'line' for instance:

Firstly, more precisely, a line is a "geometric figure formed by a point moving in a fixed direction." [dictionary definition]

In terms of the third element [plane], a line is created when two planes intersect (for example where wall meets ceiling).

More generally: a line is a long, thin mark on a surface. The term can relate to a boundary (fence) or limit, a queue, a wrinkle as a sign of aging, telephone, fishing, poetry, music, flirting, lifeline, product line, etc. It's a fairly fluid concept.

In early stages of geometry, the plane is purely passive - a home to the points and lines created on it. Let us focus on the point and lines and we can see a polar character.

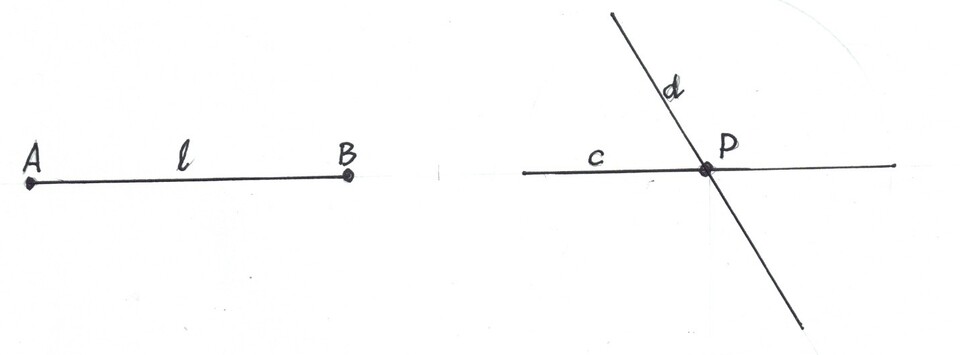

- Two Points, A and B, on the plane can be united by Line, l;

- Two Lines,c and d, drawn on the plane can intersect in a Point, P.

Union and Intersection.

Take it further:

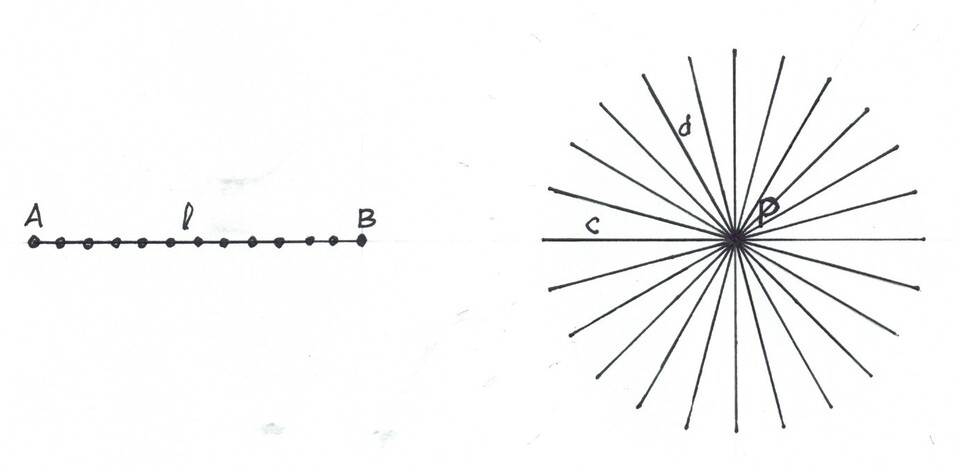

The Line uniting two Points contains myriad points (only a few are shown in the diagram). Bringing it into action, we could say the a moving point starting at A traces out a line, l, of intermediate points on its way to B. The Line holds or contains all the points.

Also, the Point, P, created by the Intersection of two lines, c and d, can hold a myriad lines that can go in every conceivable direction to every point in the universe. The only thing that the lines have in common is the Intersection Point.

Going back to Steiner's experience: these diagrams only start to have meaning when we start to think about them. Indeed, what we pereive of the world through our physical senses only begins to gain meaning for us through the spiritual activity of thinking, whereby we build concepts that truely correspond to the percepts.

Every person builds their own set of concepts through personal life experience. But our concepts and thoughts are mere shadows of a Spiritual Archetype out of which things are created.

Nearly everyone has their own concept of a straight line, each slightly different, but each an expression of a cosmic spiritual archetype of a "straight line". Geometry was the discipline that enabled Rudolf Steiner to understand that.

RB